There’s

no denying it. Food is so hot right now. Especially if it’s local,

organic, and held proudly by a small child with rosy cheeks. This is

good. Food is important. The revival of interest in real food and where

it comes from is reflected in the snack gardens in schools filled with

sugarsnap peas and lettuces, the popularity of backyard gardening, and

living walls adding life to hi-rises. Please, let it be noted that I am a

yea-sayer to all this activity.

But...well...sometimes,

there is something important missing in this whole scene. And that’s

urban farming. And I don’t just mean some school kids growing 50kg of

potatoes, or you tending some herbs on your balcony -- though both

things make me happy. I mean production gardens. Small farms and

regular-sized farmers who grow good amounts of food to feed

neighborhoods. This is a scale and an element of our food system which

needs talking about, needs valuing, and needs to be realised.

When

this is mentioned, there is often a respectful muttering of “cuba” and

“self-sufficiency”. Yep, Cubans grow a helluva lot of food in their

cities. Millions of tonnes per year. And they make an enviable amount

of compost. Yes, they had to. Yes, they were embargoed. Yet this is often where the daydreaming ends. And we head off to

buy some lettuce that travelled a few hundred kms by supermarket truck

to have the privilege of being in our salad. Maybe, we wonder, the sort

of city-based, well-orchestrated food system that Cuba boasts only

materialises when people are starving and when there is an autocratic

government to organise people into teams and land into gardens? Well,

not necessarily. There’s an alternative plotline.

First,

we need to start imagining our city bursting with food; good,

plentiful, delicious abundance. A city dotted with farms started by

enterprising, hardworking farmers dedicated to growing a lettuce which

doesn’t get carsick on the way to the store. A lettuce that you pick up

along with your weekly share of produce which is carried home on your

bike, in your backpack. You get the point: it’s grown near where you

live. This imagining takes some work. Sometimes it’s hard to see the

food forest for all the uncompromising asphalt. City farms might not

look like little scenes of bucolic loveliness nestled into a hillside,

surrounded by pasture and doe-eyed cows. But they will be beautiful all

the same, as integrated systems that combine age-old-know-how with

cutting edge technology. Food systems that take inspiration from

farmers all over the world. We have the internet and we will use it

wisely. And these systems will just keep getting more elegant. People

will stop measuring their food in miles and start walking and riding to

their local farm, whistling cheerfully, the wind in their hair, the sun

on their backs... Ok, I’ll stop now.

Seriously, these farms will not only provide gold-standard food for

your mouths. They will create livelihoods for the farmers and others who

make it all happen. Farming, especially on a small scale where your

body is your tractor, is hard work. Days can be long, wet, hot, and

exhausting. Days can also be gorgeous, warm, and filled with satisfying

labour, good conversation, and bird calls. Either way, you don’t want to

fit a farm enterprise around a full-time off-farm job, not when you

have a few hundred mouths to feed. It needs to provide you with a

livelihood.

I

used to manage a community garden. Every day held new discoveries,

learning and connections. The focus was on engaging kids and adults with

the soil, with living plants, with cooking something grown from seed

and serving it proudly to the community. That community garden remains

as much a playground of ideas as anything. A place of focus where people

can contribute, can argue, try new things, test something out, make

mistakes, eat, get distracted, meet someone new, learn something, forget

what they learned and just a place to hang around in. Especially if you

don't really have anywhere else to go. And while we would load up a

harvest table with whatever was ready (always plenty of silverbeet),

this was not a production garden for many reasons - it’s size, it’s

organisation, it’s volunteer base, and most importantly because of the

aim of the garden. This was not a garden to feed people.

It

seems obvious when it’s spelled out like that. But too often the

excitement (duly felt) about community gardens, pop-up mall vege patches

and guerilla gardening can get in the way of thinking about what

systems could, would fill our larders with enough to eat each week. And

an urban farm is probably not going to pump out the food if the farm is

relying on volunteer labour alone. “But what about the whole good-vibes

community thing?”, you ask (perhaps more eloquently).

A

farm is a community resource. Local businesses likewise. Organisations

that provide a service to the people - a useful place, a place where

people meet, things to be utilised. A place that provides livelihoods

and lively neighborhoods. We do have examples here in Australia… just

not enough of them.

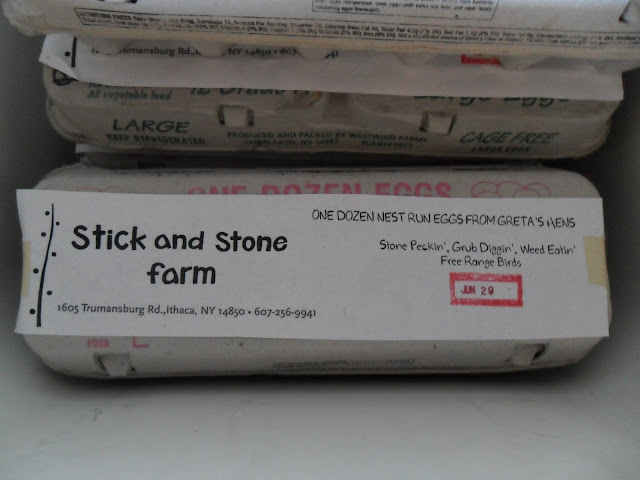

While

visiting farms in the states I spent a couple of days at Sweet Land

Farm, a CSA farm in Trumansberg, upstate New York, that feeds 350

families in their community. This is a farm started by a couple as a

business. A business with solid ethics and an actual, written-down, list

of what they are not willing to compromise, in terms of values, in

their business. They employ people who learn and practice skills in crop

planning, transplanting, harvesting, and produce handling. Men and

women who often end up starting their own small farms. I was already

impressed. But more so when it came to be CSA share pick-up day. As

people rolled in, some with kids in tow (who quickly made for the U-pick

strawberry patch) to collect their food for the week, I saw community. I

saw people connect who met through their connection to this farm,

swapping news, recipes, and smalltalk. I saw people making a tangible

connection with their food choices. They can actually touch the farm

(and the farmer, if they are feeling cheeky). They can pick their share

of peas, and their share of blue cornflowers. They can ask the farmers

about squash varieties and their plans for the future seasons. They see

what food production is about. The work. The dirt. The sweat. The

people.

"Farmers

need a place to farm and make a viable living. Farmland needs to be

enriched and nurtured so that it can yield bountiful harvests year after

year. Members need a dependable source of vibrant, richly grown food.

All of these needs must be kept in balance. Sweet Land Farm is a

CSA-only farm, so everything that we grow is for you, the shareholders.

This makes the above-mentioned balance nicely transparent"

(Sweet Land Farm member handbook)

It’s

a business and a community resource. Sure, Sweet Land Farm is a pretty

big farm, sitting on the outskirts of a pretty small town; but the same

connection of people to place, to community, to food can happen right

here in our cities, in our suburbs. People are pretty good at getting

innovative and working with smaller areas. They grow stuff on rooftops,

in laneways, in vacant quarter acre lots, laid out like mini farms -

with wheel-hoes instead of tractors. In fact, having less space forces

people to be more creative, more innovative in growing food. There are a

lot of brains working on this puzzle already.

Urban

farming is not the answer to the big question of how to feed ourselves,

dare I say it, sustainably. It’s just a really useful, and

underutilised part of the food system. And there will be crops that will

be grown on farms outside cities - grains and seed crops that make more

sense on a larger scale. But perishable vegetables, those that are at

their snap-juicing-sweetest heights when they travel only a metre from

plant to mouth should be grown as close to that mouth as possible. Have

you ever grown strawberries? Snow peas? Radishes? Try it (taste it) and

prove me wrong.

So

where to from here? For starters let’s start valuing farmers and

farm-work. I mean individually, and as a city. In the last year, in Hobart, someone

got around $27,000 in subsidies for an artificial ice skating rink business (that’s

about to be superseded a year down the track). Now I like ice skating as

much as the next guy (though I prefer glistening, real ice) but I care a

lot more about what’s for dinner. How about support for enterprising

farmers, who want to grow good food for their community? And, yes, earn a

livelihood in doing so. I’m ok with my money going to that corner.

We

need farmers and we need them to be able to sustain themselves and

their families. We need new farmers. We need farming to be an attractive

prospect to young people thinking ‘what do I want to be when I grow

up?’. We have the means, we have the ways, we all just need to get on

board with this. We, local and state government staff (including town planners and policy makers), home gardeners, small-hold farmers, community/school

gardeners, agricultural scientists, and eaters of food. That pretty much covers everyone,

right?

Let’s

not just wait patiently for our supply of food from the mainland to get

held up indefinitely, for the moment when you find shelves empty and

produce aisles lacking. Let’s not wait for an embargo, a disaster.

That’s no time to get organised, to innovate (though invariably it will

happen then too). Now is the time. It’s not simply food for thought,

it’s food forethought.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Post-script: Nov 2015. It's happening!!! Go to www.hobartcityfarm.com or www.chuffed.org/project/hobartcityfarm to find out more about a city farm in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------